TURNING INSERTS

PARTING AND GROOVING

TIP DRILLS

INDEXEABLE INSERT DRILLS

SOLID CARBIDE DRILLS

COMPATIBLE INSERTS

SPARE PARTS & ACCESSORIES

Thread turning is a precise manufacturing technique that requires specific technical terminology. These terms are essential for understanding thread geometry and production. The following explains the most important technical expressions that every turner and designer should know.

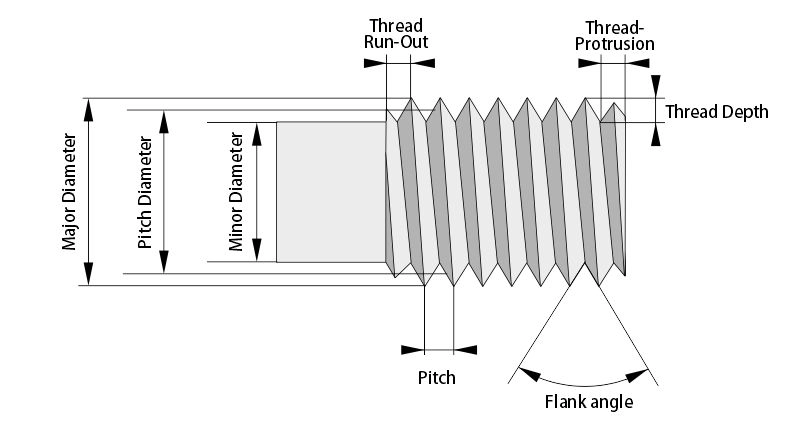

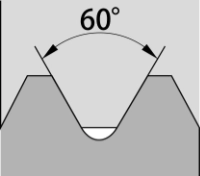

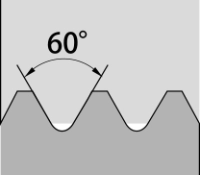

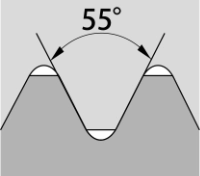

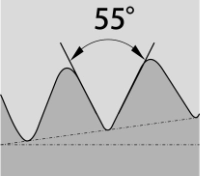

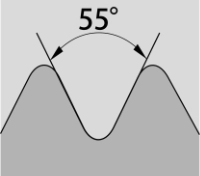

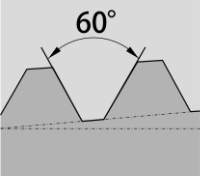

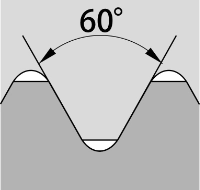

The flank angle refers to the angle between the two thread flanks, measured in an axial section through the thread. It is a characteristic feature of each thread type and significantly determines the mechanical properties of the thread. For metric threads, the flank angle is 60°, while Whitworth threads have a flank angle of 55°. A larger flank angle leads to better force transmission, while a smaller angle results in higher self-locking properties.

The pitch (P) is the axial distance between two adjacent thread turns, measured parallel to the thread axis. It indicates how far a screw moves in the axial direction during one complete revolution. A small pitch means a fine thread with many turns per unit length, while a large pitch characterizes a coarse thread with few turns.

Right-hand threads are the standard threads used, where the screw screws into the counterpart when turned clockwise (viewed from the screw head side). The mnemonic rule is: "Right tight, left loose." Left-hand threads work in reverse – they screw in when turned counterclockwise. Left-hand threads are used in special applications, for example with rotating parts where a right-hand thread would loosen itself through the rotational movement, or in safety applications for mix-up prevention.

Thread depth is the radial distance between the thread crest (major diameter) and the thread root (minor diameter). It determines the strength of the thread and the size of the load-bearing cross-sectional area. Greater thread depth leads to higher strength but also makes the thread more sensitive to damage. Thread depth is directly related to pitch and flank angle.

The major diameter is the largest diameter of the external thread, measured over the thread crests. It corresponds to the nominal diameter of the thread and is used for designation. The minor diameter is the smallest diameter of the external thread, measured at the thread root. It is crucial for the tensile strength of the screw, as this is where the smallest cross-section occurs. The difference between major and minor diameter corresponds to twice the thread depth.

The pitch diameter is the diameter of the thread at the point where the thread width equals the groove width. It lies geometrically between the major and minor diameter and is crucial for determining the fit. When measuring threads, the pitch diameter is often controlled, as it determines the actual fit between internal and external threads.

Threads per Inch (TPI) is the Anglo-Saxon designation for the number of thread turns per inch of length. This specification is used in American and British thread standards and corresponds to the reciprocal of the metric pitch. A thread with 20 TPI has a pitch of 1.27 mm (25.4 mm ÷ 20), for example. The TPI specification is particularly important when working with imported machines or when repairing older equipment.

Thread protrusion refers to the length of thread that extends beyond the component to be screwed. Sufficient protrusion is important for secure fastening and should be at least 1.5 times the screw diameter. Thread run-out is the area at the end of the thread where the thread depth gradually decreases. A clean run-out prevents damage during screwing and unscrewing and facilitates assembly.

Thread quality is defined by tolerance classes that specify the permissible deviations from nominal dimensions. For metric threads, tolerance classes such as 6H for internal threads and 6g for external threads are used. The number indicates the tolerance size, the letter indicates the position of the tolerance. Tighter tolerances (smaller numbers) lead to more precise but harder-to-manufacture threads, while wider tolerances facilitate manufacturing but offer less precision.

Multi-start threads consist of several parallel thread paths arranged offset around the thread axis. They enable faster axial movement at the same rotational speed, as the effective pitch is multiplied by the number of starts. A two-start thread with 2 mm pitch per start moves 4 mm per revolution, for example. Multi-start threads are used in quick-clamp devices, valves, and lead screws.

Thread pitch errors arise from manufacturing inaccuracies and lead to deviations from the target pitch. They can cause stress, increased wear, and malfunctions. Pitch errors are minimized through precise machine tools, correct feed settings, and regular inspection of the lead screw. In critical applications, pitch accuracy must be controlled through special measurement procedures.

A thread relief is a groove at the thread end that enables a clean thread run-out and protects the thread cutting tool. It prevents the tool from being damaged when reaching a shoulder. Washers distribute the clamping force evenly and protect the workpiece surface. They are particularly important with soft materials or large holes to prevent deformation and ensure uniform force distribution.

Threads are a central connecting element in engineering – whether in piping, mechanical engineering, or aviation. However, not every thread is the same: There are different standards and norms that differ in form, dimensions, and application area. In this article, we present the most common thread types.

The metric ISO thread is today the most widely used thread standard worldwide. It is characterized by its simple designation: M10 means an external diameter of 10 millimeters, for example. The flank angle is 60 degrees, which ensures good force transmission. Metric threads are found in almost all areas of technology, from the automotive industry to household appliances.

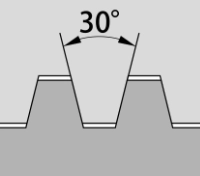

The trapezoidal thread is a special thread form for force transmission – particularly in movable machine parts such as spindles, vises, or lifting devices. It has a trapezoidal profile with a flank angle of 30 degrees, which can absorb higher axial forces than a normal screw thread. The designation is made with "Tr", e.g., Tr20x4 (external diameter 20mm, pitch 4mm). Trapezoidal threads are cylindrical and standardized according to DIN 103.

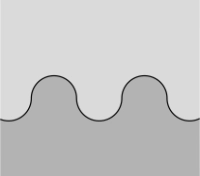

Round threads have a semicircular profile and are particularly robust against contamination and damage. They are mainly used in harsh environments where other threads would wear out quickly. Typical applications are railway couplings, fire extinguishing equipment, and military equipment. The great advantage lies in easy cleaning and high resistance to mechanical influences. Round threads are designated according to DIN 405, for example Rd 40x4, where "40" is the external diameter and "4" is the pitch in mm.

The Whitworth thread is a British standard and belongs to the oldest standardized threads. It was introduced in the 19th century and was the standard in Great Britain and the Commonwealth for a long time. Here too, the flank angle is 55°, which distinguishes it from the more modern metric ISO thread.

BSP pipe threads (British Standard Pipe) are a British standard for pipe connections based on the Whitworth thread profile. They are divided into two main variants (described individually below): BSPP (parallel) and BSPT (tapered). Both use a flank angle of 55° and are specified in inch dimensions, e.g., 1/2" BSP. BSP threads are widespread in Europe and Asia and are used particularly in hydraulics, pneumatics, and sanitary technology. The designation "BSP" is often used as a general term for BSPP and BSPT.

The BSPT thread is a tapered pipe thread according to British standard (British Standard Pipe Taper). It is mainly used in the field of compressed air, hydraulics, and gas installations – particularly in Europe and Asia. The thread flanks have an angle of 55°, and due to the tapered form, a tight connection is created when screwing in – often without additional sealant.

The BSPP thread (British Standard Pipe Parallel) is a cylindrical pipe thread according to British standard. Unlike BSPT, it is not tapered but straight. The sealing therefore does not occur via the thread itself, but with a sealing ring (e.g., O-ring) or a flat seal at the thread end. It also uses a 55° flank angle and is based on the Whitworth profile. Thread sizes are specified in inches, e.g., G 1/2 (where "G" indicates the BSPP version).

The NPT thread is the US-American counterpart to BSPT. It is also tapered and suitable for pressure-tight connections – however, according to the ANSI/ASME standard. The flank angle is 60°, which distinguishes NPT from BSPT. Important: BSPT and NPT are not compatible, although they look similar..

UN threads are metrically named inch threads according to the North American standard "Unified Thread Standard". They are available in various versions:

UN threads are cylindrical (not tapered) and are mainly used in mechanical and automotive engineering in the USA.

The choice of the right thread type is crucial for a secure, tight, and durable connection. Those who work internationally or deal with different standards should know the differences between NPT, BSPT, UN, UNC, and Whitworth. Even though they look optically similar, they are not always technically compatible – and this can lead to leaks or damage.

If you are unsure about the selection of a thread, it is worth looking at the technical data or consulting with the manufacturer.

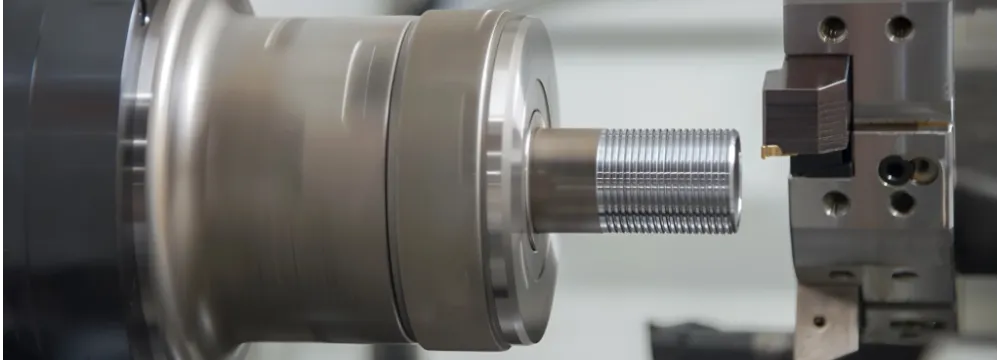

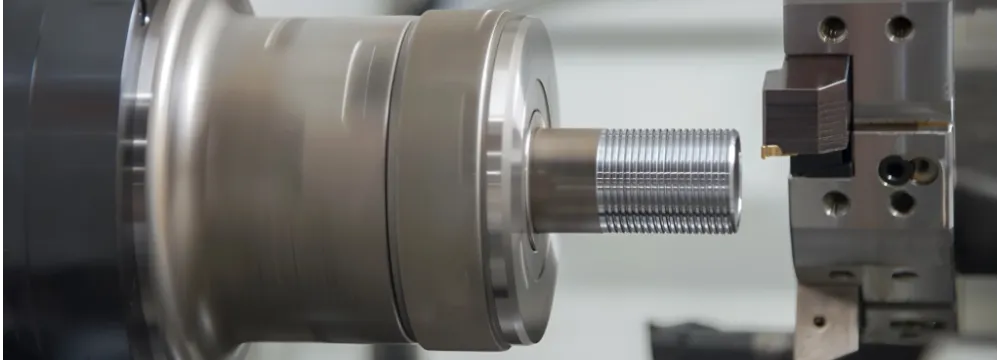

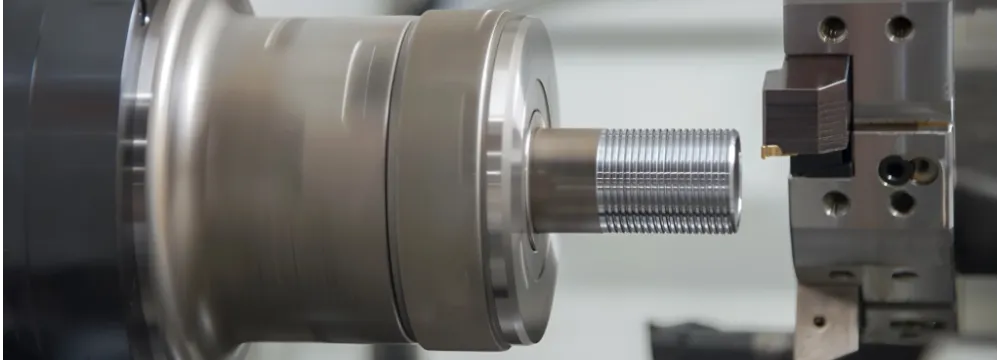

Thread turning is a chip-removing manufacturing process for producing internal and external threads on lathes. A profiled turning tool is used to turn the thread profile into the workpiece. The quality of the thread depends significantly on the chosen infeed method, cutting parameters, and correct tool geometry.

In external thread turning, the thread is created on the outer surface of a shaft or bolt. The thread turning tool moves from outside to inside and cuts the profile spirally into the rotating workpiece.

Internal thread turning is performed in pre-drilled holes with special internal thread turning tools. These are usually narrower due to limited space conditions and require special attention for chip removal.

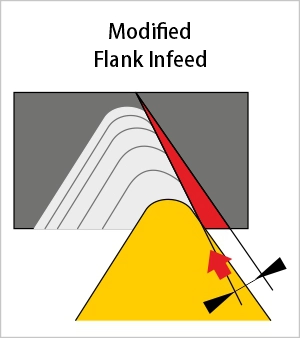

In this method, the infeed is not radial but along one of the thread flanks, usually the trailing flank.

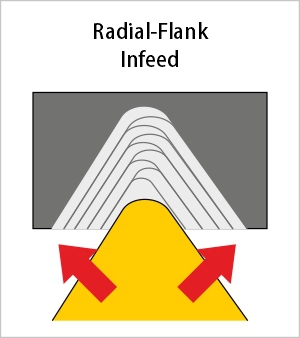

The classic method where infeed occurs perpendicular to the workpiece axis.

Combination of radial infeed for rough machining and flank infeed for finish machining.

Thread turning requires precise settings and careful planning. The choice of suitable infeed method depends on the material, quality requirements, and available time. Modern CNC lathes enable high precision and repeatability, provided the fundamental principles are observed.

On CNC lathes, right-hand threads are created through programmed synchronization between spindle speed and feed rate. The precise electronic control enables highly accurate and reproducible threads.

G-Code Basic Command: G33 or G32 for simple thread cuts, G76 for complete threading cycles.

Example Programming:

G76 P030060 Q100 R0.05

G76 X18.0 Z-30.0 P1500 Q500 F2.0

Parameter Meanings:

Tool selection:Special thread cutting inserts or solid carbide threading tools with 60° cutting angle for metric threads.

Tool correction:

Precise input of tool geometry into the tool correction table of the CNC control. Exact tip radius compensation is crucial for thread quality.

Multi-stage cutting:

The CNC control automatically divides the total cut into multiple passes. Roughing and finishing passes are distinguished.

Cut distribution:

Large cutting depths at the beginning, finer passes for finishing. The final infeed is often performed as an air cut for surface improvement.

Spindle synchronization:

Constant synchronization between main spindle and feed axes via encoder feedback ensures exact pitch.

Modern CNC machines often feature integrated measurement systems for direct thread control. Additionally, inspection is performed using thread gauges or tactile measuring devices.

On CNC lathes, left-hand threads are created by reversing the spindle rotation direction or by specifying a negative pitch in the program. The electronic control system ensures exact synchronization between the spindle and feed axes.

For left-hand threads, the pitch is programmed negatively or the spindle rotation direction is reversed.

Example Programming Method 1 (negative pitch):

G76 P030060 Q100 R0.05G76 X18.0 Z-30.0 P1500 Q500 F-2.0

Example Programming Method 2 (reversed rotation direction):

M04 (spindle left)G76 P030060 Q100 R0.05G76 X18.0 Z-30.0 P1500 Q500 F2.0M03 (back to right rotation)

Control-dependent syntax: Depending on the CNC control system (Fanuc, Siemens, Heidenhain), different parameters or commands may be required.

Tool correction: The tool geometry must be adapted according to the cutting direction. With reversed spindle rotation direction, the effective tool geometry changes.

Special tools: Special indexable inserts or appropriately oriented tools are often used for left-hand threads.

Tool holder: When reversing the spindle rotation direction, the tool holder must be able to safely absorb the changed cutting forces.

Cycle programming:

Modern CNC controls offer special cycles for left-hand threads with automatic adjustment of all parameters.

Collision avoidance:

The control system automatically monitors tool movements and prevents collisions with reversed rotation direction.

Quality control:

Integrated measuring systems can precisely measure and document left-hand threads as well.

For critical applications, a test run at reduced speed is recommended to verify correct programming and tool alignment.

The right-hand thread is the standard thread in machining. It rotates clockwise into the nut and follows the rule "righty tighty, lefty loosey". On the conventional lathe, it is created by synchronous movement of the main spindle and feed carriage.

Rotation direction: The main spindle runs forward (clockwise), while the tool carriage moves from left to right.

Gear ratio: The correct gear ratio between the main spindle and lead screw is set via the change gear train. For metric threads: Pitch = feed per revolution of the main spindle.

Tool setting: The thread cutting tool is set with a cutting angle of 60° for metric threads. The tool edge must be positioned exactly at spindle height and aligned perpendicular to the workpiece axis.

The thread cutting is performed in several passes with progressively increasing cutting depth. The first cut serves as a guide cut with shallow depth (approx. 0.1-0.2 mm). The threading dial is engaged, and the tool follows the pitch predetermined by the lead screw.

The thread pitch is checked with a thread gauge or template. The finished thread must thread smoothly and without binding into a corresponding nut thread. Any burrs are removed with a deburring tool.

In a left-hand thread, the threaded screw rotates counterclockwise into the nut. On the conventional lathe, this requires a reversed approach compared to the standard right-hand thread.

Rotation direction: The main spindle must run backwards (counterclockwise), while the tool carriage is moved from right to left.

Lead screw: The rotation direction of the lead screw must be adjusted accordingly. This is done via the change gear train or by changing the feed direction.

Tool setting: The thread cutting tool is set as a mirror image of the right-hand thread. The cutting angle remains at 60° for metric threads, but the tool geometry is oriented in reverse.

The cutting process is performed in several passes with increasing cutting depth. Special attention must be paid to timely disengagement at the thread end, as the tool carriage moves in the reverse direction.

Important note: The tool must re-engage at exactly the same point to avoid flank offset. The lathe's threading dial helps maintain the correct position.

The thread pitch is checked with a thread gauge or a corresponding left-hand thread counterpart. The finished thread must thread counterclockwise into a matching nut thread.

| External Tool Holder | TER |

| Insert | 16/22 ER |

| Main application | Threading |

| Right/Left | Right |

| Clamping | Screw Clamp |

| Cooling | With Cooling Holes |

| Packaging Unit | 1 Pc. |

| H | h | L | B | f | |

| SER 1616 F16-H | 16 | 16 | 100 | 16 | 16 |

| SER 2020 H16-H | 20 | 20 | 125 | 20 | 20 |

| SER 2525 K16-H | 25 | 25 | 125 | 25 | 25 |

| SER 3232 K16-H | 25 | 25 | 125 | 25 | 25 |

| SER 2525 K22-H | 25 | 25 | 125 | 25 | 25 |

| SER 3232 K22-H | 32 | 32 | 125 | 32 | 32 |

| External Tool Holder | SEL |

| Insert | 16/22 EL |

| Main application | Threading |

| Right/Left | Left |

| Clamping | Screw Clamp |

| Cooling | With Cooling Holes |

| Packaging Unit | 1 Pc. |

| H | h | L | B | f | |

| SEL 1616 F16-H | 16 | 16 | 100 | 16 | 16 |

| SEL 2020 H16-H | 20 | 20 | 125 | 20 | 20 |

| SEL 2525 K16-H | 25 | 25 | 125 | 25 | 25 |

| SEL 3232 K16-H | 25 | 25 | 125 | 25 | 25 |

| SEL 2525 K22-H | 25 | 25 | 125 | 25 | 25 |

| SEL 3232 K22-H | 32 | 32 | 125 | 32 | 32 |

| Boring Bar | SIR |

| Insert | 11/16/22 IR |

| Right/Left | Right |

| Main application | Threading |

| Clamping | Screw Clamp |

| Cooling | With Cooling Hole |

| Packaging Unit | 1 Pc. |

| d | b | L | h | f | L1 | Dmin | |

| SIR-16 K11-H | 16 | 15,5 | 125 | 15 | 10 | 20,9 | 12 |

| SIR-16 M11-H | 16 | 16 | 150 | 15 | 10,5 | 25,9 | 16 |

| SIR-16 M16-H | 16 | 15,5 | 150 | 15 | 12 | 27 | 20 |

| SIR-20 M16-H | 20 | 19 | 150 | 18 | 14 | 28,7 | 25 |

| SIR-20 Q16-H | 20 | 19 | 180 | 18 | 14 | 34 | 25 |

| SIR-25 M16-H | 25 | 24 | 150 | 23 | 17 | 28,8 | 32 |

| SIR-32 R16-H | 32 | 31 | 200 | 30 | 22 | 30,9 | 40 |

| SIR-32 S16-H | 32 | 31 | 250 | 30 | 22 | 30,9 | 40 |

| SIR-40 T16-H | 40 | 38,5 | 300 | 37 | 27 | 31,5 | 50 |

| SIR-20 Q22-H | 20 | 19 | 180 | 18 | 15 | 35 | 25 |

| SIR-25 R22-H | 25 | 24 | 200 | 23 | 19 | 39 | 32 |

| SIR-32 S22-H | 32 | 31 | 250 | 30 | 22 | 36,4 | 40 |

| SIR-40 T22-H | 40 | 38,5 | 300 | 37 | 27 | 37,2 | 50 |

| Boring Bar | SIL/TIL |

| Insert | 11/16/22 IL |

| Main application | Threading |

| Right/Left | Left |

| Clamping | Screw Clamp |

| Cooling | Without Cooling Holes |

| Packaging Unit | 1 Pc. |

| d | b | L | h | f | L1 | Dmin | Insert | |

| SIL-16 K11-H | 16 | 15,5 | 125 | 15 | 10 | 20,9 | 12 | 11 IL |

| SIL-16 M11-H | 16 | 16 | 150 | 15 | 10,5 | 25,9 | 16 | 11 IL |

| SIL-16 M16-H | 16 | 15,5 | 150 | 15 | 12 | 27 | 20 | 11 IL |

| SIL-20 M16-H | 20 | 19 | 150 | 18 | 14 | 28,7 | 25 | 16 IL |

| SIL-20 Q16-H | 20 | 19 | 180 | 18 | 14 | 34 | 25 | 16 IL |

| SIL-25 M16-H | 25 | 24 | 150 | 23 | 17 | 28,8 | 32 | 16 IL |

| SIL-32 R16-H | 32 | 31 | 200 | 30 | 22 | 30,9 | 40 | 16 IL |

| SIL-32 S16-H | 32 | 31 | 250 | 30 | 22 | 30,9 | 40 | 16 IL |

| SIL-40 T16-H | 40 | 38,5 | 300 | 37 | 27 | 31,5 | 50 | 16 IL |

| SIL-20 Q22-H | 20 | 19 | 180 | 18 | 15 | 35 | 25 | 22 IL |

| SIL-25 R22-H | 25 | 24 | 200 | 23 | 19 | 39 | 32 | 22 IL |

| SIL-32 S22-H | 32 | 31 | 250 | 30 | 22 | 36,4 | 40 | 22 IL |

| SIL-40 T22-H | 40 | 38,5 | 300 | 37 | 27 | 37,2 | 50 | 22 IL |

| Insert size | 16 |

| Inside/Outside Thread | Outside |

| Direction | Right |

| Thread Type | Metric |

| Profile | Full profile |

| Workpiece Materials | Steel, Stainless Steel, Special Materials, NF-Metals |

| Flank angle | 60° |

| Grade | RT315: PVD-coated P15-P25 and M10-M25 solid carbide for universal use |

| Packaging Unit | 2 pc. |

| ISO | Pitch | I.C | S | d | |

| 16ER-V-ISO-1,0-G RT315 | 16 | 1,0mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16ER-V-ISO-1,25-G RT315 |

16 | 1,25mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16ER-V-ISO-1,5-G RT315 |

16 | 1,5mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16ER-V-ISO-1,75-G RT315 |

16 | 1,75mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16ER-V-ISO-2,0-G RT315 |

16 | 2,0mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16ER-V-ISO-2,5-G RT315 |

16 | 2,5mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16ER-V-ISO-3,0-G RT315 |

16 | 3,0mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| Insert size | 16 |

| Inside/Outside Thread | Inside |

| Direction | Right |

| Thread Type | Metric |

| Profile | Full profile |

| Workpiece Materials | Steel, Stainless Steel, Special Materials, NF-Metals |

| Flank angle | 60° |

| Grade | RT315: PVD-coated P15-P25 and M10-M25 for universal use |

| Packaging Unit | 2 pc. |

| ISO | Pitch | I.C | S | d | |

| 16IR-V-ISO-1,0-G RT315 | 16 | 1,0 mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16IR-V-ISO-1,25-G RT315 |

16 | 1,25 mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16IR-V-ISO-1,5-G RT315 |

16 | 1,5 mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16IR-V-ISO-1,75-G RT315 |

16 | 1,75 mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16IR-V-ISO-2,0-G RT315 |

16 | 2,0 mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16IR-V-ISO-2,5-G RT315 |

16 | 2,5 mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16IR-V-ISO-3,0-G RT315 |

16 | 3,0 mm | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| Insert size | 16 |

| Inside/Outside Thread | Outside |

| Direction | Right |

| Thread Type | Imperial |

| Profile | Part Profile |

| Workpiece Materials | Steel, Stainless Steel, Special Materials, NF-Metals |

| Flank angle | 55° |

| Grade | RT315: PVD-coated P15-P25 and M10-M25 solid carbide for universal use |

| Packaging Unit | 2 pc. |

| ISO | TPI | I.C. | S | d | |

| 16ER-T-A55-G RT315 |

16 | 48-16 TPI | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16ER-T-AG55-G RT315 |

16 | 48-8 TPI | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16ER-T-G55-G RT315 |

16 | 14-8 TPI | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| Insert size | 16 |

| Inside/Outside Thread | Inside |

| Direction | Right |

| Thread Type | Imperial |

| Profile | Part Profile |

| Workpiece Materials | Steel, Stainless Steel, Special Materials, NF-Metals |

| Flank angle | 55° |

| Grade | RT315: PVD-coated P15-P25 and M10-M25 solid carbide for universal use |

| Packaging Unit | 2 pc. |

| ISO | TPI | I.C. | S | d | |

| 16IR-T-AG55-G RT315 |

16 | 48-16 TPI | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16IR-T-AG55-G RT315 |

16 | 48-8 TPI | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

| 16IR-T-AG55-G RT315 |

16 | 14-8 TPI | 9,525 | 3,52 | 4 |

Categories